Airplane Racer Sues Ubisoft and Ivory Tower for Including Distinctive Racing Airplane in "The Crew 2"

BIG PICTURE

Earlier this month, an airplane racer sued Ubisoft and its developer, Ivory Tower, for allegedly misappropriating his “identity” by including his allegedly famous airplane in The Crew 2. This case presents unique facts and, hopefully, an opportunity to push right of publicity law in the right direction, towards greater First Amendment protection for video game developers.

BILL “TIGER” DESTEFANI AND HIS PLANE, STREGA

Plaintiff Bill G. Destefani, also known as “Tiger,” has raced airplanes in California for forty years. Now 75 years old, Destefani won the “Gold” unlimited race at the National Championship Air Races in 1987, 1992, 1993, 1995, 1996, 1997 and 2008. In 2009, 2010, 2012, 2015, and 2017, Destefani “handpicked” other pilots to fly in his famous “Strega” airplane and they, too, won gold. Destefani acquired “Strega” (which means “witch” in Italian), a highly modified P-51 Mustang originally flown by the Royal Australian Air Force, in 1945.

Destefani claims that “Strega” is highly distinctive and known by “a unique constellation of identifying features,” including:

a unique paint job

a stylized number “7” of the tail

an image of the Italian flag behind the cockpit

Destefani’s name in script font underneath the cockpit

the stylized word “Strega” on the front of the airplane near the nose

Destefani claims that over his 40+ year racing career, he and Strega have become “famous in the aeronautics and airplane exhibition industries and among consumers in those industries.” In other words, “Strega and Destefani are inexorably linked.”

In addition, Destefani registered the word “Strega” as a trademark in 1991.

DESTEFANI’S ALLEGATIONS

Developed by Ivory Tower and published by Ubisoft for Windows, PS4, Xbox One and Stadia, The Crew 2 is a racing game that was first released on June 29, 2018. Destefani alleges that Ubisoft marketed the game with several key statements, including:

The game “takes you and your friends on a reckless ride inside a massive, open-world recreation of the United States.”

Unlike the original The Crew game, which only featured cars, Ubisoft allegedly advertises that The Crew 2 allows players to “[e]xperience the thrill of intense motorsports action in a car, truck, motorcycle, boat, off-road buggy, or even a stunt plane!”

The Crew 2 advertises that players can “[c]heck out some of the most iconic vehicles you will be able to ride,” which includes a virtual copy of Strega.

Destefani alleges that Ivory Tower even copied his actual, real-world sponsors, including the primary sponsor for a particular time period, “Palazzo Estates” (along side of the fuselage) and secondary sponsors AeroShell and Roush Aviation (on the front of the fuselage near the nose). Destefani also alleges that Ubisoft’s game website advertises the plane as “NORTH AMERICAN - P51 Mustang(tm) STREGA(tm) 1945,” without referring to Destefani as a trademark owner.

Destefani seems particularly salty that: (1) defendants did obtain trademark permission from other brand owners with products featured in the game such as Harley Davidson (and attributed them), but didn’t do so for him and Strega; and (2) that Ivory Tower did change some existing brands in the game, including the famous Wynn Hotel in Vegas to the “Win” Palace.

Destefani claims that the defendants violated both his statutory and common law right of publicity under California law. He also has claims for False Endorsement (15 U.S.C. § 1125(a)) based on using “personally identifying attributes” of his identity, Trademark Infringement, and unfair competition.

THE TRADEMARK CLAIMS

Since Destefani sued in the Central District of California, we will first look at how Ubisoft and Ivory Tower could move to dismiss using Ninth Circuit and California precedents. The first case that comes to mind, since both involved similar legal claims and professional racers, is VIRAG, S.R.L. v. Sony Computer Entm't Am. LLC, 699 F. App'x 667 (9th Cir. 2017).

In Virag, Mirco Virag, a professional race-car driver, and his eponymous, Italian flooring company, VIRAG, S.R.L., sued Sony for including the VIRAG trademark on a banner on a bridge over the realistic racetrack in Sony’s Gran Turismo 5 and Gran Turismo 6 games. The district court dismissed VIRAG, S.R.L.’s right of publicity claim because corporations cannot assert a right of publicity, but declined to dismiss Mirco Virag’s individual right of publicity claim. The district court also dismissed the trademark infringement and false designation of origin claims under the Lanham Act after applying the Rogers test. As the district court observed, “under the Rogers test, the Lanham Act should not be applied to expressive works (1) unless the use of the trademark or other identifying material has no artistic relevance to the underlying work whatsoever, or, (2) if it has some artistic relevance, unless the trademark or other identifying material explicitly misleads as to the source or the content of the work.”

Interestingly, in the Virag case, Virag agreed to voluntarily dismiss his right of publicity claim with prejudice so that he and VIRAG, S.R.L. could immediately appeal the district court’s dismissal of the Lanham Act claims. This, it turned out, was not a good strategy.

On appeal, (which again only focused on the Lanham Act claims), the Ninth Circuit agreed that the Rogers test barred the plaintiff’s claims because “Sony’s use of the VIRAG trademark furthers its goal of realism, a legitimate artistic goal […] and therefore satisfies the requirement that Sony's use of the trademark have ‘above zero’ artistic relevance to the Gran Turismo games.” On the second prong, the Ninth Circuit found that “Sony’s use of the VIRAG trademark meets the second requirement of Rogers, because VIRAG does not allege any ‘explicit indication, overt claim, or explicit misstatement’ that would cause consumer confusion.” Sony then moved for its attorney’s fees.

For Destefani, the Virag case presents a substantial obstacle for his Lanham Act claims. The Rogers standard is extremely permissive. Not only is there an easy case to be made for “artistic relevance” (an extremely low bar to begin with), but the complaint also lacks allegations sufficient (at least in my view) to constitute something “explicitly misleading” as to the source or the content of the work. Since the unfair competition claim is really just a throwaway, that then leaves the right of publicity claims.

RIGHT OF PUBLICITY CLAIMS

Destefani can probably make a prima facie claim for violation of his right of publicity. In an even older racing right of publicity case, the Ninth Circuit addressed a Tobacco company’s advertisement featuring a red race car with distinctive white pin-striping and an oval medallion with a white background that was allegedly “exclusive” to the race car driven by famous racer, Lothar Motschenbacher. Motschenbacher v. R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Co., 498 F.2d 821, 827 (9th Cir.1974). In Motschenbacher, the Ninth Circuit reviewed a district court’s granting of summary judgment. It faulted the district court for failing “to attribute proper significance to the distinctive decorations appearing on the car” in determining whether the racecar driver’s identity had been used, even though his actual likeness hadn’t been featured. The Ninth Circuit didn’t actually decide the issue, but instead remanded the case back to the district court for further proceedings. Later Ninth Circuit opinions, however, including Virag, cite the Motschenbacher case as standing for the proposition that you can invoke someone’s right of publicity without actually showing their likeness or using their name.

In some ways, Destefani’s case is stronger than the case in Motschenbacher because The Crew 2 has a plane that actually has his name on it. This then raises the big question: Is the use of Strega “transformative” and therefore protected by the First Amendment?

THE TRANSFORMATIVE USE TEST

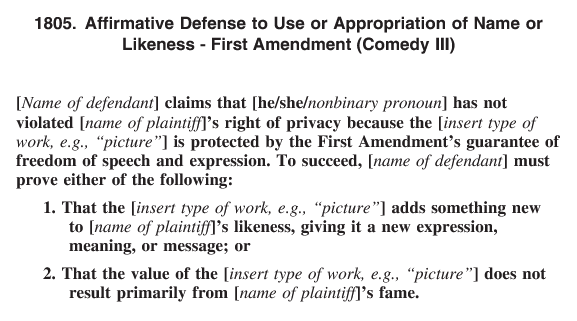

Let’s pretend, for starters, that we know nothing about right of publicity jurisprudence and just skip to the jury instructions. If a California jury had to decide this First Amendment defense, how would a court instruct them? Like this:

Given these instructions, we might argue about the first point, but on the second point, it seems hard to argue that the “value” of The Crew 2 results primarily from Destefani’s fame.

Unfortunately for Ubisoft and Ivory Tower, courts deciding right of publicity cases on motions for summary judgment or motions to dismiss, do not follow clear and easy instructions like this. The Ninth Circuit, applying California’s Comedy III test, looks at “whether the work in question adds significant creative elements so as to be transformed into something more than a mere celebrity likeness or imitation.” To assess this, it evaluates five factors:

First, if “the celebrity likeness is one of the ‘raw materials’ from which an original work is synthesized,” it is more likely to be transformative than if “the depiction or imitation of the celebrity is the very sum and substance of the work in question.”

Second, the work is protected if it is “primarily the defendant’s own expression”— as long as that expression is “something other than the likeness of the celebrity.” This factor requires an examination of whether a likely purchaser’s primary motivation is to buy a reproduction of the celebrity, or to buy the expressive work of that artist.

Third, to avoid making judgments concerning “the quality of the artistic contribution,” a court should conduct an inquiry “more quantitative than qualitative” and ask “whether the literal and imitative or the creative elements predominate in the work.”

Fourth, the California Supreme Court indicated that “a subsidiary inquiry” would be useful in close cases: whether “the marketability and economic value of the challenged work derive primarily from the fame of the celebrity depicted.”

Lastly, “when an artist’s skill and talent is manifestly subordinated to the overall goal of creating a conventional portrait of a celebrity so as to commercially exploit his or her fame,” the work is not transformative.

Super easy and clear, right?

If this was a person being put into a video game, we might analogize to the Hart and Keller NCAA football cases (which both applied the Comedy III factors and found that EA’s use of the athlete’s likeness was not transformative). In each case, the majority drew a bright line rule (which was heavily criticized by the dissent) against game developers literally recreating the celebrity “in the very setting in which he has achieved renown.” If we begin with the premise that a distinctive vehicle can invoke someone’s identity (Motschenbacher); and the rule that you aren’t allowed to recreate a celebrity’s identity in the very setting in which he achieved renown (Hart and Keller); does that lead to the conclusion that including the “Strega” in The Crew 2 isn’t “transformative”?

Not necessarily.

For one thing, the Ninth Circuit in Motschenbacher didn’t decide that the race car used in the tobacco advertisement was an unlawful use of the driver’s identity. It simply said that the court erred in failing to consider whether a distinctive race car could be considered a use of a person’s identity for purposes of making a right of publicity claim. In that case the cigarette company’s use of the car in its TV advertisement actually “caused some persons to think the car in question was plaintiff's and to infer that the person driving the car was the plaintiff.” Here, Destefani doesn’t allege any similar facts and, moreover, he alleges that numerous other racers raced in Strega — and even won many races — for many years. This leaves ample room to argue both (a) that the game developers did not include Strega to invoke Destefani’s identity; and (b) that there is no reason to believe the public viewed the use as invoking Destefani’s identity.

Of course, we could delve into further arguments about how Hart and Keller were wrongly decided and how more recent decisions like Sarver v. Chartier, 813 F.3d 891 (9th Cir. 2016) — which, while rightly decided, also had incorrect reasoning and analysis — get closer to where the law should be. However, the smarter course for the defendants may be to just give the trial court an easy way to dismiss the complaint without having to worry about correcting the gigantic mess that is right of publicity jurisprudence.