SUMMARY

In a follow up to a previous post, a Northern District of California judge found a video game patent asserted against Sony invalid as non-patentable subject matter.

THE SETUP

In August 2019, Bot M8 LLC, a patent assertion entity, sued three Sony entities for infringement of six different patents in the Southern District of New York. The case was transferred to the Northern District of California where four of the six patents were dismissed, as discussed previously.

Sony moved for summary judgment of non-infringement and section 101 invalidity of one of the two remaining patents, U.S. Patent No. 7,338,363.

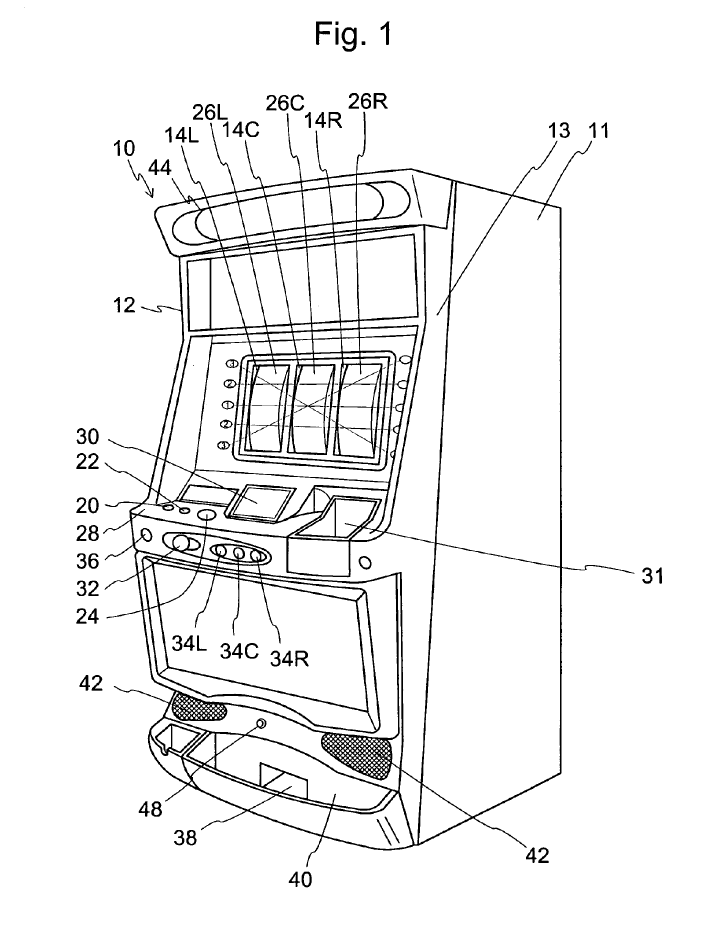

The ’363 patent entitled “GAMING MACHINE, SERVER, AND PROGRAM” derived from slot machine games (see Fig. 1 below).

The basic premise of the ’363 patent is to connect multiple gaming machines and allow player results to be aggregated. The aggregated results could be used in future games. In the slot machine example, if one player was on a losing streak but the aggregate results of multiple players was positive, the system could provide better jackpot odds. While the ’363 patent mostly refers to slot machine type gams, the claims are directed to any type of gaming machine.

Bot M8 alleged that Sony’s MLB The Show 19; Uncharted 4: A Thief’s End; and Uncharted: Lost Legacy games infringed. In particular, Bot M8 alleged that the Uncharted games infringed the patents because players could unlock advanced and more powerful weapons in multiplayer modes.

MOTION FOR SUMMARY JUDGMENT

On April 23, 2020, Sony filed its motion for summary judgment arguing both that none of the accused games infringed Claim 1 of the ’363 patent (the only asserted claim) and that Claim 1 of the ’363 patent was invalid under 35 U.S.C. § 101 due to failure to claim patentable subject matter. On June 10, 2020, the court ruled on Sony’s motion.

BRIEF BACKGROUND ON 35 U.S.C. § 101

Prior to the Supreme Court decision in Alice Corp. v. CLS Bank International, 573 U.S. 208 (2014), software was rarely challenged as unpatentable. Alice changed that and set forth a two part test to determine if the patent is directed to ineligible subject matter. First, is the patent directed to an abstract idea? If so, do the claimed elements transform the claims into something patent-eligible? If the answer to both questions is “no,” then the claimed invention is not patentable. Since Alice, hundreds of claims have been invalidated under 35 U.S.C. § 101.

Sony argued that the ’363 patent was directed to the abstract idea of “adding numbers (i.e., ‘game results’) in order to generate further numbers (i.e., ‘total result’ and ‘specification value’).” This seems overly reductionist, but counsel for accused infringers often try to cast a patent’s claims as abstractly as possible. Perhaps acknowledging just how far Sony had gone, the court stated “a court must not oversimplify the invention” and quoted the Supreme Court’s warning against over-abstracting claims stating, “[a]t some level, all inventions...embody, use, reflect, rest upon, or apply laws of nature, natural phenomena, or abstract ideas.” Nevertheless, the court ultimately agreed that the ’363 patent was directed to the abstract idea of “a game machine that updates the game conditions based on past results to keep players engaged.” In reaching this conclusion, the court started from the idea that “the invention must be concrete,” and found that the patent did not claim specific ways to accomplish the abstract idea:

At the most specific, claim 1 of the ’363 patent doesn’t actually teach how to increase or decrease the difficulty of a slot machine, or any gaming machine for that matter, based on prior results to keep players engaged.

Having found that the ’363 patent was directed to an abstract idea, the court then turned to see if the claim elements had additional features that would transform an abstract idea into something patentable. Here, the court found that the claim elements merely described “generic and functional hardware” to accomplish their abstract tasks. The order of the claim elements can transform an invention into patentable subject matter, but the court found nothing in Claim 1 to add to patentability.

The court concluded that ’363 patent failed the Alice analysis and granted Sony’s motion for summary judgment with respect to the invalidity of the ’363 patent. Because the patent was invalid, the court denied Sony’s other arguments as moot.

SIDE NOTE

In Bot M8’s opposition to Sony’s motion for summary judgment, Bot M8 makes the interesting argument that because Sony has obtained similar patents on “manipulating data for entertainment purposes” that “it defies credibility that Sony could suggest that entertainment-related inventions are ineligible.” Some might categorize this argument as unclean hands, I’d call it whataboutism. In any case, the court gave the argument short shrift:

Life is too short to litigate Sony’s own patents here. If Sony’s patents are invalid for the reasons articulated herein, patent owner is free to cite this order in an appropriate proceeding. For our present purposes, however, two wrongs don’t make a right.